The silence often hangs heavy in the air, broken only by the rustle of robes, the chime of a bell, or the faint echo of chanted prayers. For centuries, convents and monasteries have stood as fortresses of faith, learning, and self-sufficiency – intricate worlds built not just for spiritual devotion, but for an entire way of life. If you've ever gazed upon the venerable stone walls of an abbey and wondered about the daily rhythms that unfolded within, you're about to explore the precise, often ingenious, architecture and layout of a typical convent or monastery's functional spaces.

These weren't just buildings; they were meticulously planned ecosystems, designed to foster community, solitude, and unwavering purpose. From the grand, soaring church to the humble sleeping quarters, every stone, every archway, every drainage channel served a vital role in sustaining a monastic community, shaping the very soul of its inhabitants.

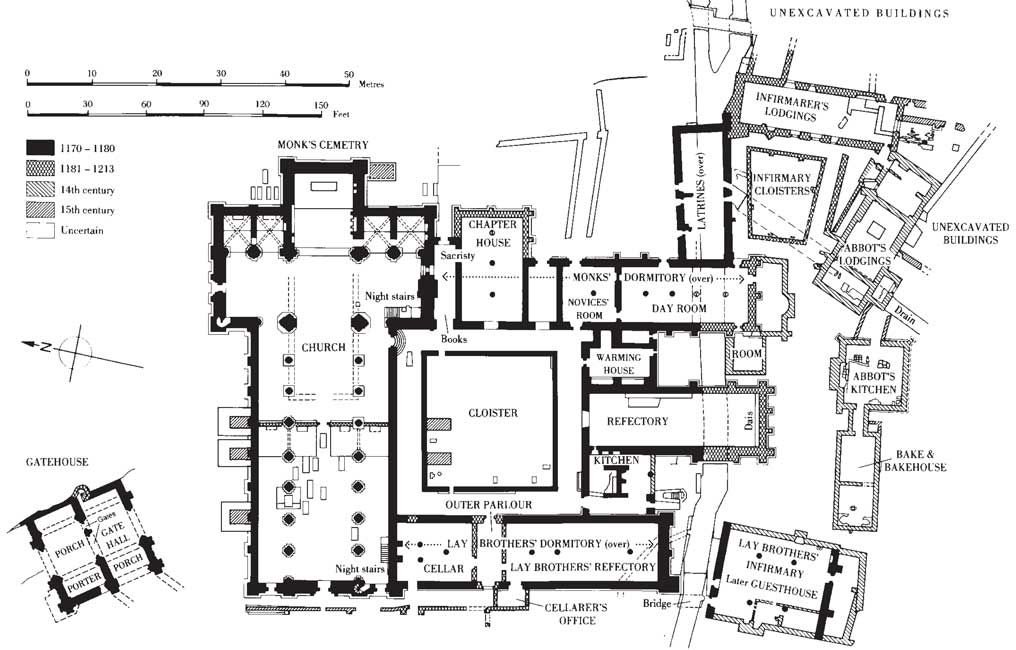

At a Glance: The Monastic Blueprint

- Heart of the Community: The cloister, an enclosed courtyard, served as the central hub for work, teaching, and quiet reflection.

- Spiritual Core: A large, cruciform church, often oriented east-west, was the focal point for worship and public services.

- Mind & Spirit: Libraries and scriptoriums were vital learning centers, preserving knowledge and producing illuminated manuscripts.

- Daily Sustenance: The refectory (dining hall), kitchens, and storerooms supported communal meals.

- Rest & Routine: Dormitories and individual cells provided minimal comfort for monks and nuns, often with direct access to the church for night prayers.

- Health & Hygiene: Infirmaries offered medical care, while advanced sanitation systems like reredorters (latrines) and bathhouses were surprisingly sophisticated.

- Administration & Warmth: Chapter houses facilitated daily meetings and governance, while the calefectory offered a rare heated space.

- Self-Sufficiency: Workshops, mills, bakeries, and guesthouses allowed abbeys to operate as self-contained villages, sometimes even mini-economies.

- Security: High walls and sometimes fortress-like designs protected these communities and their resources.

The Blueprint of Sacred Living: An Evolution of Purpose

Imagine a community designed for introspection, devotion, and collective work, where every structure supports a singular, holy mission. That's the essence of a convent or monastery. These communities, originating in the 4th century in places like Egypt and Syria, spread across the Byzantine Empire and into Europe by the 5th century. Saint Benedict of Nursia, active around 480-543 AD, laid down the foundational "Rule" that would largely shape the European monastic model, emphasizing stability, obedience, and work.

Early abbeys, often built in remote, even isolated locations like mountaintops or islands, prioritized solitude and protection. Think of the breathtaking monasteries of Meteora, Greece, clinging precariously to cliffsides like fortresses. But as they grew, so did their influence. By the High Middle Ages, abbeys became central to secular communities, hubs of learning, charity, and commerce, evolving into impressive, wealthy stone structures that often spurred the growth of surrounding villages and towns.

The architecture was never arbitrary. As historian J. L. Singman noted, monasticism was marked by "planning, coordination, and even deliberate standardisation." Whether drawing on ancient Roman villas or Byzantine prototypes (which featured wall-surrounded complexes with courtyards, a central church, and multi-story living quarters), European abbeys, from Celtic to Carolingian to Norman periods, evolved a remarkably consistent design language. This wasn't just about aesthetics; it was about function, efficiency, and adhering to the specific rules of an order.

The Heart of the Abbey: The Cloister

If a monastery is a body, the cloister is its beating heart. Derived from the Latin "claustrum," meaning "enclosed space," this arcaded walkway surrounding an open square, or garth, was the communal nucleus. Think of it as the ultimate tranquil quad, off-limits to outsiders, a serene haven for introspection and daily activities.

Typically entered from the northwest, the cloister wasn't just for contemplation; it was a vibrant, though quiet, hub. Monks or nuns would converse here (usually in regulated silence), teach novices and oblates, and perform various chores. The central garth, often a verdant garden or featuring a calming water element, provided both beauty and practical space. For particularly large monasteries, or those desiring more intense solitude, a "lesser cloister" might offer an additional, even quieter retreat. Carthusian abbeys, known for their stricter, hermit-like living, paradoxically featured some of the largest cloisters, serving as a primary communal space due to their emphasis on individual isolation even within a community.

The Spiritual Nexus: The Abbey Church

Connected directly to the cloister, often strategically positioned to shield it from cold northern winds, stood the abbey church. This was, without question, the spiritual and architectural crown jewel, typically cruciform (cross-shaped) in plan and oriented along an east-west axis.

The main entrance, usually on the west side, was often a grand affair. Imagine multiple doorways, soaring lancet windows, sometimes a stunning rose window, and niches filled with statues of saints. These churches weren't static; they grew progressively larger and grander over the centuries. Naves, the main body of the church for public attendance and processions, increased in length and width. The east wing, in particular, extended to house ever-larger choirs of monks, often separated from the public by an ornate screen. Beyond the choir lay the presbytery, home to the sacred altar.

The eastern end, whether semicircular or square, frequently featured tall, exquisite stained-glass windows. These weren't just decorative; they depicted local stories, revered founders, or even highlighted precious relics, which might be displayed in the presbytery, sometimes watched over by a monk in a lofty position. Wealthy benefactors often funded chantries – memorial chapels or altars – for perpetual masses in their name, further enriching the church's architectural fabric. Dominating the skyline, a belfry tower called inhabitants to prayer, its extension a clear signal of the abbey's prosperity, as seen in Fountains Abbey's impressive 170-foot tower by the 16th century.

Spaces for Mind & Soul: Education and Contemplation

Monasteries were the intellectual powerhouses of the medieval world, acting as crucial local learning centers. At the heart of this was the library, a sacred repository of knowledge. Here, extensive collections of books, accumulated through donations or the tireless labor of monastic scribes, resided in carefully constructed wall recesses. These weren't just religious texts; they included ancient classical works, meticulously preserved for posterity.

Often facing south for optimal light and warmth, the library was closely linked to the scriptorium, the workshop where monks dedicated themselves to writing and copying manuscripts. Seated at individual carrels, they produced not just copies of texts, but often stunning illuminated manuscripts, turning practical work into an art form. These scholarly endeavors went beyond the cloister walls; abbeys educated the children of the wealthy and meticulously trained their novices. Some, like Whitby Abbey, gained renown for even training bishops, a testament to their academic rigor. You might even find royal archives held safely within these walls. And it wasn't just men; medieval nuns, like the visionary Hildegard of Bingen, were also prolific copiers of books and skilled in intricate needlework.

Daily Life & Sustenance: Practical Quarters

Life in an abbey revolved around a structured rhythm of prayer, work, and communal living, supported by a range of practical spaces.

The refectory, or frater, was the communal dining hall. Imagine long wooden tables where inhabitants typically enjoyed one main meal daily in summer and two in winter. The abbot, prior, and any distinguished guests would sit on a raised platform, overlooking the community. A pulpit in a corner allowed for scripture readings during meals, fostering a continuation of spiritual focus even during daily sustenance. For those orders with slightly relaxed dietary rules, a misericord might exist—a separate room designated for the consumption of meat, a food usually forbidden to monks and nuns. Before entering, a lavabo, a stone basin, provided water for ritual handwashing, announced by a small bell. Refectories were often large, rectangular buildings along one side of the cloister, later sometimes extended for more space, with grand examples like Cluny's featuring 36 glazed windows and intricate wall paintings.

Adjacent to the refectory, you'd find the kitchens and storerooms, the nerve center for food preparation and provisioning. Beyond these, the calefectory was a welcome respite—often the only heated room apart from the kitchens, offering warmth from November to Easter.

Abbeys were also pioneering centers for medical care. Hospitals or infirmaries catered not only to ill or aged monks but sometimes included a second wing for outsiders. This commitment to healing underscored their mission of charity. Specialized workshops housed skilled craftworkers—shoemakers, smiths, carpenters—producing necessary goods for the community. An almonry distributed alms to the poor, and a separate room often facilitated trade, reflecting the abbey's economic activity.

Rest, Reflection, and Routine: Residential & Administrative Zones

The residential quarters within a convent or monastery were designed for minimal comfort, reinforcing the monastic vows of poverty and detachment. Discover where nuns live and you'll often find an emphasis on simplicity.

Dormitories, or dorters, were common, with novices and full members often segregated. Beds were stark, typically featuring straw or feather mattresses and simple wool blankets. Later dormitories saw the introduction of wooden cubicles, offering a degree of individual privacy. Cluny Abbey's dormitory was notably advanced for its time, boasting 97 glazed windows and oil lamps to ensure no monk slept in darkness. A common and practical feature was a staircase leading directly from the dormitory to the church, allowing for easy access to night services.

However, stricter orders sometimes diverged significantly. Carthusian monks, for example, lived in individual houses within the monastic precinct. These were remarkably self-contained units, each with its own fireplace, living room, study, workshop, bathroom, water tap, and even a private garden, designed to preserve an almost complete solitude. Food was often delivered via hatches, minimizing direct interaction.

By the High Middle Ages, many manual tasks were performed by lay brothers, laborers, or serfs. These individuals lived in separate blocks, often with their own kitchens where foods disallowed for the monks (like meat) could be prepared. You might even find disgraced nobles forced into retirement within abbey walls.

For visitors, hospitality buildings were essential. Pilgrims and ordinary travelers found accommodation in dedicated rooms, often located west of the cloister. Distinguished visitors, however, enjoyed more palatial apartments, frequently situated in the gatehouse. As abbeys grew in wealth and influence, the abbot or abbess often acquired increasingly grand, separate accommodation by the 13th century, reflecting their absolute authority.

Every morning, usually around 8 a.m., the community gathered in the chapter house. This large, often ornate room was where all residents convened to discuss abbey affairs, confess transgressions, and receive their daily duties after a reading from the founder's rule book. It was the administrative and judicial heart of the community, where decisions were made and spiritual discipline maintained. The early Benedictine Monastery of St Gall, for instance, used the north walk of its cloisters for this purpose before dedicated chapter houses became standard.

Advanced Amenities: Sanitation and Water

For the medieval period, monastic sanitation was remarkably advanced, a testament to careful planning and a need for communal health.

Toilets, or reredorters, were typically connected directly to the dormitories for convenience, especially during the night. Cluny Abbey, again, stands out with a latrine block featuring 45 cubicles, each with its own window, all designed to empty efficiently into drainage channels fed by diverted streams. This integration of natural water sources for waste removal was a hallmark of monastic engineering. While bathing was infrequent for most (perhaps 2-3 times a year unless ill), larger abbeys often had dedicated bathhouses, another sign of their commitment to the welfare of their inhabitants. Beyond this, fountains and other water features were not just decorative but provided fresh, running water for various daily needs.

Beyond the Walls: The Abbey's Broader Footprint

A defining feature of any convent or monastery was its enclosing abbey wall. This wasn't just for security and protection from raiders (a real concern during 9th-10th century Viking raids), but also symbolized the spiritual enclosure, setting the sacred space apart from the secular world. The wall often featured an elaborate portal or gatehouse, serving as the controlled entry point.

Within or just outside these walls, a cemetery was always present, typically located east of the church. These were divided, with designated sections for members of the order and wealthier local benefactors. Prominent figures like abbots were often interred within the church itself, reflecting their status.

The Benedictine Monastery of St Gall, with its detailed 820 AD plan, offers a remarkable glimpse into the self-sufficient nature of a large abbey. Its design included a mill, bakehouse, stables, and various workshops—a veritable village in itself. This plan explicitly shows a cruciform church as the nucleus, with the cloister to its south, and monastic buildings (refectory, dormitory, calefactory) arranged around it. The infirmary and novices' school were to the east, while the outer school and abbot's house were placed outside the main enclosure. Hospitality was carefully segmented, with separate buildings for distinguished guests, poor travelers, and visiting monks. Workshops, a granary, mills, and stables completed the complex, showcasing a comprehensive approach to communal living and production. Westminster Abbey, another Benedictine foundation, mirrored this general arrangement, with its cloister and monastic buildings predominantly to the south of its magnificent church.

Enduring Legacy: Decline, Adaptation, and Survival

From the mid-14th century onwards, the golden age of abbeys began to wane. Factors like the Black Death, devastating famines, the collapse of serfdom, and increasingly, the covetous eyes of rulers seeking monastic wealth led to a decline. Most notoriously, Henry VIII's dissolution of monasteries in Britain, beginning in 1536, saw the systematic dismantling of these once-mighty institutions.

While a few abbeys were repurposed and elevated to cathedrals (think Chester, Canterbury, Westminster, and Durham), the vast majority met a less fortunate end. They became picturesque ruins, their valuable stone plundered for other constructions. In Continental Europe, many were converted into hotels, hospitals, schools, or art galleries, finding new life beyond their original sacred purpose. Some vanished entirely, replaced by secular properties that nonetheless retained names like "The Abbey," a whisper of their former grandeur.

Yet, the legacy endures. Some abbeys, like Westminster Abbey in London or the breathtaking monasteries of Meteora in Greece, continue their religious function today, living testaments to an architectural and spiritual tradition that has shaped civilizations for over a millennium. They stand as powerful reminders of the meticulous planning, profound purpose, and enduring faith that literally built these extraordinary structures.

Navigating the Past: What to Look For Today

When you visit the ruins or active complexes of a convent or monastery today, you're not just looking at old stones; you're tracing the blueprint of an entire civilization. Here's how to engage with these sites like an expert:

- Locate the Cloister: Start here. It's the central point and will help you orient yourself. Notice the arcade, the garth, and how other key buildings connect to it.

- Identify the Church: Look for the grandest, often cruciform, structure. Try to discern the nave, choir, and presbytery, imagining the monks or nuns at prayer. Can you spot any remnants of a belfry tower?

- Trace the Daily Routine: From the cloister, consider where the refectory would have been (often along one side), and the dormitory (often connecting directly to the church). Think about the "why" behind the placement of each space.

- Seek the Functional Spaces: Look for signs of the chapter house (often to the east of the cloister), the calefectory, and even the remnants of a reredorter or infirmary. These functional areas reveal the practicality underpinning the spiritual life.

- Appreciate the Engineering: Notice the water channels, drainage systems, and evidence of workshops or mills. These elements speak to the self-sufficiency and advanced planning of these communities.

- Ponder the Walls: Observe the enclosing walls and the gatehouse. Imagine the contrast between the bustling outside world and the serene, ordered life within.

Understanding the architecture and layout of a typical convent or monastery isn't just an exercise in history; it's an immersive journey into the very soul of medieval life, revealing how devotion, discipline, and ingenious design created spaces that have resonated through the centuries.